Please note: This post discusses suicide and self-harm and may be distressing for some readers. If you or someone you know is experiencing thoughts of suicide, you are not alone. Help is available through the U.S. national suicide and crisis helpline—call or text 988 or chat online at 988lifeline.org.

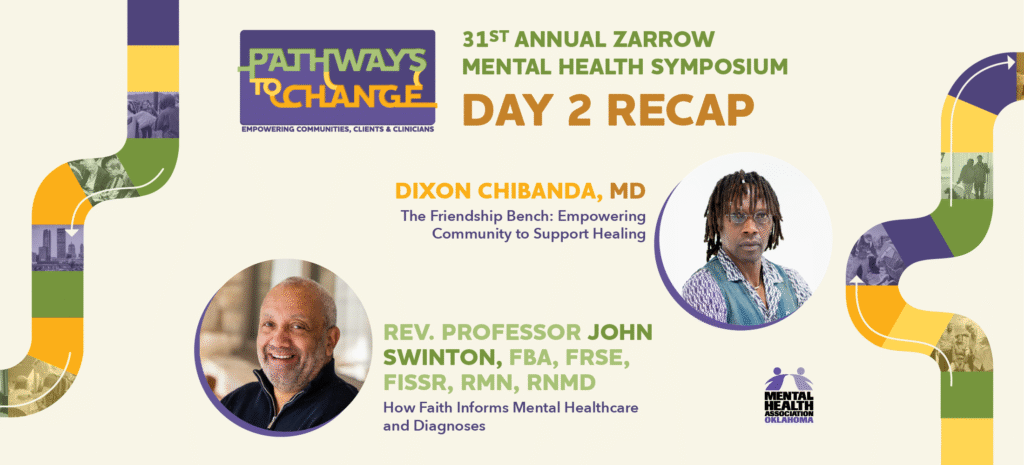

Day Two of the 31st Annual Zarrow Mental Health Symposium brought global perspectives to mental health and healing. In addition to more than 20 breakout sessions, attendees learned from two internationally recognized leaders in the field: Dr. Dixon Chibanda presented from his home in Zimbabwe, with “The Friendship Bench: Empowering Community to Support Healing.” The afternoon’s keynote was led by Rev. Dr. John Swinton, speaking from the United Kingdom, with his presentation, “How Faith Informs Mental Healthcare and Diagnoses.”

The Friendship Bench

Dr. Dixon Chibanda’s keynote presentation focused on his groundbreaking community-based mental health initiative. The idea for The Friendship Bench was born from deep personal loss. Erica, a patient of Dr. Chibanda’s for two years, knew she needed help, but her family could not afford the bus fare for the 100-mile journey to his hospital. She died by suicide while her parents were still trying to gather the money.

Determined to make care more accessible, Dr. Chibanda sought to expand mental health care beyond hospital walls and into communities. The answer, for him, was to equip “regular folks”—specifically grandmothers—to provide listening and loving guidance to those experiencing loneliness, depression, and suicidality.

What began with 14 grandmothers has since grown into a network of more than 300,000 trained grandmothers across Zimbabwe, with Friendship Bench programs now active in multiple countries, including the United States.

In Zimbabwe, as in many parts of the world, grandmothers are grounded in their communities as “custodians of local culture and wisdom.” With limited access to psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, and therapists, equipping trusted community members with the tools to listen and respond effectively has become a powerful solution.

Extensive, peer-reviewed research supports the model’s success: participants report reduced symptoms of depression and anxiety, while the grandmothers themselves experience improved resilience and lower rates of hypertension, diabetes, and depression compared to their peers. Dr. Chibanda attributes those outcomes to a renewed sense of purpose, connection, and belonging. In short, they have a reason to get up in the morning and the satisfaction of a job well done at the end of the day.

For those hoping to start similar programs, Dr. Chibanda emphasized that “anyone can be a safe space—the key lies in knowing how to be.” His approach requires expressed empathy—the ability to make people feel respected and understood—the ability to use the power of silence as a tool, and the consistent and correct use of screening tools to identify clients who are at the highest risk of self-harm. In his words, “when you create a safe space using expressed empathy—where people can genuinely open up and feel vulnerable—you create an element of hope. And that is when healing can actually begin.”

To learn more about The Friendship Bench, visit their website or read Dr. Chibanda’s book, The Friendship Bench: How Fourteen Grandmothers Inspired a Mental Health Revolution.

How Faith Informs Mental Healthcare and Diagnoses

Rev. Dr. John Swinton serves as Professor in Practical Theology and Pastoral Care and Chair in Divinity and Religious Studies at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland. Before his career in academia, Dr. Swinton worked as a mental health nurse, caring for patients who, as he described, “see the world differently.”

Working alongside those patients, he found himself asking profound questions: “What does it mean to have faith in God, when you’ve forgotten who God is? What does it mean to know God when you lack the cognitive capacity to understand faith?” Those questions became the foundation for his theological work.

Dr. Swinton encouraged the audience to rethink how we define and describe mental illness, dementia, and depression, because how we describe something impacts how it is perceived, and how it is perceived influences how we respond. He argued that a person’s sense of self or personhood should never be diminished by a diagnosis.

While many define mental illness as the absence of health, Dr. Swinton offered a more hopeful alternative. Viewing illness as simply “the lack of health,” he said, removes the possibility of ever experiencing wholeness. Instead, he urged the pursuit of peace—peace within one’s mind, peace with others, and peace with creation and God. True health, he suggested, is not the absence of illness, but the presence of God, meaningful relationships, and community.

These ideas extend beyond mental illness to include cognitive conditions such as dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Individuals with these diagnoses often experience a profound loss of personhood in societies that prize intellect and memory. As memories fade, so too can the social roles that once defined them—mother, father, husband, wife, teacher, neighbor, friend. This loss can be both culturally and emotionally devastating, leaving individuals feeling forgotten or discarded by their own communities.

Dr. Swinton urged clinicians, service providers, caregivers, and loved ones to redefine how we approach cognitive and mental health challenges. “We are not just our brains or our memories,” he reminded attendees. Healing begins by helping people rediscover a sense of “homefulness”—a feeling of belonging and emotional safety, where one is truly seen, valued, and at peace.

In mental healthcare, according to Dr. Swinton, “our goal should be to create a space where individuals can feel at home, respected, and free to be themselves even in the midst of their storms.”

To learn more, read Dr. John Swinton’s books, Seeking Sanctuary, Finding Shalom and Dementia: Living in the Memories of God.

Tomorrow promises to be another inspiring day of learning and connection. It’s not too late to register! Attendees can access all conference content—including the keynotes detailed above—online through the end of the year. Register now at zarrowsymposium.org.

Segundo día del 31º Simposio Anual de Salud Mental de Zarrow: Perspectivas globales sobre la salud mental

El segundo día del 31º Simposio Anual de Salud Mental de Zarrow trajo perspectivas globales a la salud mental y la curación. Además de más de 20 sesiones de trabajo, los asistentes aprendieron de dos líderes reconocidos internacionalmente en el campo: el Dr. Dixon Chibanda presentó desde su casa en Zimbabue, con “The Friendship Bench: Empowering Community to Support Healing”. El discurso de apertura de la tarde fue dirigido por el Rev. Dr. John Swinton, hablando desde Escocia, con su presentación, “Cómo la fe informa la salud mental y los diagnósticos”.

El Banco de la Amistad

La presentación principal del Dr. Dixon Chibanda se centró en su innovadora iniciativa de salud mental basada en la comunidad. La idea de The Friendship Bench nació de una profunda pérdida personal. Erica, paciente del Dr. Chibanda durante dos años, sabía que necesitaba ayuda, pero su familia no podía pagar el pasaje de autobús para el viaje de 100 millas a su hospital. Murió por suicidio mientras sus padres todavía intentaban reunir el dinero.

Decidido a hacer que la atención sea más accesible, el Dr. Chibanda buscó expandir la atención de salud mental más allá de las paredes del hospital y hacia las comunidades. La respuesta, para él, era equipar a la “gente común”, específicamente a las abuelas, para que escucharan y guiaran amorosamente a quienes experimentan soledad, depresión y tendencias suicidas.

Lo que comenzó con 14 abuelas se ha convertido desde entonces en una red de más de 300.000 abuelas capacitadas en todo Zimbabue, con programas de Friendship Bench ahora activos en varios países, incluido Estados Unidos.

En Zimbabue, como en muchas partes del mundo, las abuelas están arraigadas en sus comunidades como “guardianas de la cultura y la sabiduría locales”. Con acceso limitado a psiquiatras, psicólogos clínicos y terapeutas, equipar a los miembros de la comunidad de confianza con las herramientas para escuchar y responder de manera efectiva se ha convertido en una solución poderosa.

Una extensa investigación revisada por pares respalda el éxito del modelo: los participantes informan una reducción de los síntomas de depresión y ansiedad, mientras que las propias abuelas experimentan una mayor resiliencia y tasas más bajas de hipertensión, diabetes y depresión en comparación con sus compañeros. El Dr. Chibanda atribuye esos resultados a un renovado sentido de propósito, conexión y pertenencia. En definitiva, tienen un motivo para levantarse por la mañana y la satisfacción del trabajo bien hecho al final del día.

Para aquellos que esperan iniciar programas similares, el Dr. Chibanda enfatizó que “cualquiera puede ser un espacio seguro, la clave está en saber cómo ser”. Su enfoque requiere empatía expresada, la capacidad de hacer que las personas se sientan respetadas y comprendidas, la capacidad de usar el poder del silencio como herramienta y el uso consistente y correcto de herramientas de detección para identificar a los clientes que corren el mayor riesgo de autolesionarse. En sus palabras, “cuando creas un espacio seguro utilizando la empatía expresada, donde las personas pueden abrirse genuinamente y sentirse vulnerables, creas un elemento de esperanza. Y ahí es cuando realmente puede comenzar la curación”.

Para obtener más información sobre The Friendship Bench, visite su sitio web o lea el libro del Dr. Chibanda, The Friendship Bench: How Fourteen Grandmothers Inspired a Mental Health Revolution.

Cómo la fe informa la salud mental y los diagnósticos

El Rev. Dr. John Swinton se desempeña como profesor de Teología Práctica y Cuidado Pastoral y Catedrático de Divinidad y Estudios Religiosos en la Universidad de Aberdeen en Escocia. Antes de su carrera en el mundo académico, el Dr. Swinton trabajó como enfermero de salud mental, cuidando a pacientes que, como describió, “ven el mundo de manera diferente”.

Trabajando junto a esos pacientes, se encontró haciendo preguntas profundas: “¿Qué significa tener fe en Dios, cuando has olvidado quién es Dios? ¿Qué significa conocer a Dios cuando careces de la capacidad cognitiva para entender la fe?” Esas preguntas se convirtieron en la base de su trabajo teológico.

El Dr. Swinton alentó a la audiencia a repensar cómo definimos y describimos las enfermedades mentales, la demencia y la depresión, porque la forma en que describimos algo afecta la forma en que se percibe y la forma en que se percibe influye en cómo respondemos. Argumentó que el sentido de sí mismo o de la personalidad de una persona nunca debe verse disminuido por un diagnóstico.

Si bien muchos definen la enfermedad mental como la ausencia de salud, el Dr. Swinton ofreció una alternativa más esperanzadora. Ver la enfermedad simplemente como “la falta de salud”, dijo, elimina la posibilidad de experimentar la plenitud. En cambio, instó a la búsqueda de la paz: paz dentro de la mente, paz con los demás y paz con la creación y Dios. La verdadera salud, sugirió, no es la ausencia de enfermedad, sino la presencia de Dios, las relaciones significativas y la comunidad.

Estas ideas se extienden más allá de las enfermedades mentales para incluir afecciones cognitivas como la demencia y la enfermedad de Alzheimer. Las personas con estos diagnósticos a menudo experimentan una profunda pérdida de personalidad en sociedades que valoran el intelecto y la memoria. A medida que los recuerdos se desvanecen, también pueden hacerlo los roles sociales que alguna vez los definieron: madre, padre, esposo, esposa, maestro, vecino, amigo. Esta pérdida puede ser devastadora tanto cultural como emocionalmente, dejando a las personas sintiéndose olvidadas o descartadas por sus propias comunidades.

El Dr. Swinton instó a los médicos, proveedores de servicios, cuidadores y seres queridos a redefinir la forma en que abordamos los desafíos cognitivos y de salud mental. “No somos solo nuestros cerebros o nuestros recuerdos”, recordó a los asistentes. La curación comienza ayudando a las personas a redescubrir un sentido de “hogar”, un sentimiento de pertenencia y seguridad emocional, donde uno es realmente visto, valorado y en paz.

En el cuidado de la salud mental, según el Dr. Swinton, “nuestro objetivo debe ser crear un espacio donde las personas puedan sentirse como en casa, respetadas y libres de ser ellas mismas incluso en medio de sus tormentas”.

Para obtener más información, lea el libro del Dr. John Swinton, Buscando santuario, encontrando Shalom y demencia: viviendo en los recuerdos de Dios.

Mañana promete ser otro día inspirador de aprendizaje y conexión. ¡No es demasiado tarde para registrarse! Los asistentes pueden acceder a todo el contenido de la conferencia, incluidas las conferencias magistrales detalladas anteriormente, en línea hasta fin de año. Regístrese ahora en zarrowsymposium.org.